When are vacuum cups and forceps used when delivering a baby?

For an operative vaginal delivery and sometimes with a Caesarean section delivery.

Will I need an operative vaginal delivery?

Hopefully not. Only about 12% of my patients need operative vaginal deliveries.

The usual indications for an operative vaginal delivery are:

- Lack of progress in second stage labour with achieving a vaginal delivery despite maternal effort (pushing).

- Maternal exhaustion with pushing in the second stage.

- Foetal distress in the second stage labour.

- Delivery of the aftercoming head with a breech vaginal delivery.

When is it safe to do an operative vaginal delivery?

- You must be in second stage labour (cervix fully dilated). Some doctors do operative vaginal deliveries before then (while still in first stage labour), but this increases the risk considerably.

- Your baby’s head must be engaged in your pelvis. Some doctors do operative vaginal deliveries before then (when the baby’s head is not engaged), but this increases the risk considerably. I prefer the baby’s head not only to be engaged but to be as low as possible in your pelvis when doing an operative vaginal delivery. The lower it is the less traumatic an operative vaginal delivery is likely to be for your baby and you.

When do I use vacuum or forceps?

In the past

In the past forceps were much more popular that vacuum cups. My preference now is using a vacuum cup.

If using forceps which type of forceps are chosen is determined by which way the baby’s head is turned. Forceps are of different shape to suit the position to the baby’s head. Using the wrong forceps increases the difficulty and risks of the operative vaginal delivery.

- Neville Barnes Forceps If the baby’s head was looking down at the floor (direct OA – occipito-anterior position) or looking straight up (direct OP – occipito-posterior position) and the obstetrician does not want to rotate the baby’s head to OA.

- Kiellands forceps. The baby’s head needs to be rotated as it is not a direct OA or OP. If the baby’s head is direct OP and the obstetrician wants to rotate the baby’s to OA position for delivery.

- Wrigley’s forceps. When the baby’s head was very low and on view. Sometimes Wrigley’s forceps are used to deliver a baby’s head at a Caesarean section delivery.

- Piper’s forceps. To deliver the baby’s head with a breech vaginal delivery.

Now

My preference is now using a vacuum cup to facilitate an operative vaginal delivery for reasons stated below. But I do have every confidence in my expertise with forceps use.

Sometimes the vacuum cup comes off with traction for various reasons. Alter careful assessment, I usually apply forceps to complete the delivery.

I have never had a baby or mother suffer significant trauma as a consequence of an operative vaginal delivery that I have done, be it forceps or vacuum cup.

Why I prefer using a vacuum cup now for operative vaginal deliveries?

Instrumentation for doing vacuum cup deliveries has improved considerably and so vacuum cups are easier to use are more reliable than they were in the past and have advantages over forceps choice. These include:

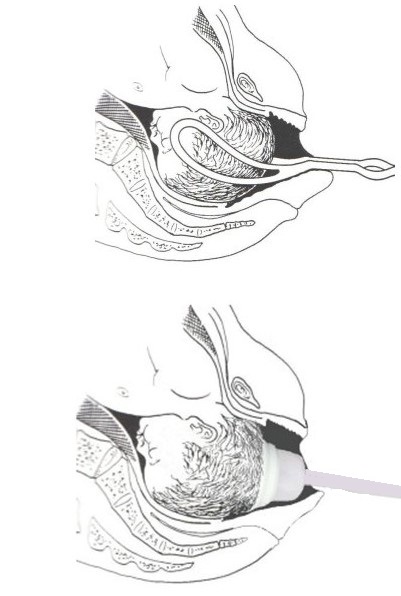

- Less discomfort for the mother. There is generally only minor discomfort with placement of the vacuum cup as the cup sits on the top of the baby’s head. Forceps sit at each side of the baby’s head, and so forceps application stretches the vagina, the vaginal entrance and the perineum. Particularly Kiellands forceps can be difficult to place and yet it is essential that they be placed correctly to minimise trauma risk to the baby and mother. Rotation of the baby’s head with Kiellands forceps can be very uncomfortable, but again it is essential that it be done correctly to minimise trauma risk to the baby and mother. Traction discomfort is greater with forceps that vacuum cup because the forceps are on the sides of the baby’s head and so stretch the vagina, the vaginal entrance and the perineum greater than just the baby’s head. What this means is that vacuum deliveries can be usually done without analgesia whereas forceps ideally should be done with an epidural block working or otherwise a pudendal nerve block and local anaesthetic infiltration of the perineum.

- Less trauma to the mother Episiotomy is routine with forceps deliveries because of the bigger diameter with the forceps at each side of the baby’s head. Despite this there can also be nasty vaginal and perineum tears. With a vacuum delivery I do not routinely do an episiotomy. As well I can facilitate a slower and more controlled delivery of the baby’s head and more gradual stretching of the perineum. Often with a vacuum delivery the perineum is often intact and there are no stitches needed.

- Less potential risk for baby. For me, because I have considerable expertise with both I do not have a challenge with either with consideration of baby’s well-being. But for a less skilled obstetrician the vacuum cup option is safer. After all, the vacuum cup will come off if the doctor pulls too hard but forceps don’t. As well the doctor must have correct positioning of the forceps to minimise the risk of trauma to the baby, and so the obstetrician must be confident about accuracy in doing a pelvic examination of a woman in second stage labour in assessing this. For vacuum use correct positioning on the baby’s head is important but not as essential.

Following a vacuum cup delivery the baby routinely has a ‘chignon’ (fluid in subcutaneous tissue below where the cup was placed), occasional a cephalhaematoma (blood in subcutaneous tissue below where the cup was placed) and occasionally scalp skin trauma. These resolve, though they don’t give the baby a pretty look after birth. Following forceps the baby often has pressure marks at the sides of the head where the forceps sat. Again these resolve. I have never done harm to a baby because of a forceps delivery

I have never had any baby experience permanent damage to the face or head following my use of forceps or vacuum. But there is increased risk of serious complications with some obstetricians and trainee obstetricians because of their lack of clinical expertise and acumen with operative vaginal deliveries.

Some obstetricians prefer using forceps rather than a vacuum cup for operative vaginal deliveries.

Which vacuum cup?

The two types available at the Norwest Private Hospital and the Sydney Adventist Hospital are:

- MityOne Cup This is my preference if the baby’s head is directly OA or OP and doesn’t need rotation. I consider it gives better traction.

- Kiwi cup This is my preference if the baby’s head needs rotation with delivery. As well I will use it if the MityOne cup comes off.

The two cups are of different shape and so have different functionality. As well obstetricians have different preferences.

Which forceps?

Today there are only Neville Barnes forceps and Kiellands forceps available in the Birth(ing) Unit. Wrigley’s forceps are available in the operating theatre for Caesarean section deliveries

Caesarean sections

I will use forceps if it is not possible to delivery baby’s head with the surgical assistant pressing down on the top of the uterus and my trying to scoop the baby’s head out with my hand in the uterus below the head. Some obstetricians always use forceps with a Caesarean section delivery.

I find often only one forceps blade is needed. The forceps blade is applied in the underside of baby’s head and is used to scoop up baby’s head with the assistant is pressing down on the top of the uterus. The forceps action is bit like a shoehorn.

I have never damaged a baby when using forceps to facilitate a Caesarean section delivery.

Irrational fear

Some pregnant women have an irrational fear of having an operative vaginal delivery, and especially of having a forceps delivery. Some express this in birth plans where they state: “operative vaginal delivery or no forceps delivery.” Some say it at an antenatal visit.

Operative vaginal deliveries, and especially forceps deliveries are potentially very dangerous. This danger is greater when the delivery is done incorrectly and/or by an inexperienced (or even no experienced), poorly or minimally trained, and minimally skilled doctor. Hence the risk is greater for women who go through the public system. As a public patient it is likely your operative vaginal delivery will be done by a trainee obstetrician who has minimal experience (or even no experience), minimal training, and minimal clinical skills. If a women books privately with a junior obstetrician, while the risk is less than if the delivery is done by a trainee obstetrician, there is greater risk than if she had booked with a senior more experienced, better trained and highly skilled senior obstetrician.

I suspect such irrational fear is most often based on social media reports from probably unknown sources and of questionable accuracy. They also ignore that by going to senior obstetrician who is very experienced, well trained and highly skilled the risks are minimised. As well, such pregnant women are indicating they have no knowledge of the increased danger to them or their baby by having such a blanket view.